Contributor: Dr. Courtney Manser, MD, CCFP (PC)

Take-Away Tidbits

- Keep in mind that trainees are already at a higher risk of grief and recognition is vital.

- When a death is expected, discuss the case with your learner. Provide end-of-life teaching when able, and prepare them as best as possible.

- Explore your own, as well as your learner’s risk factors for a grief reaction.

- Have a “post death” plan for your team as well as the learner to debrief.

- Get help yourself, and encourage the learner to seek help if you are concerned about grief.

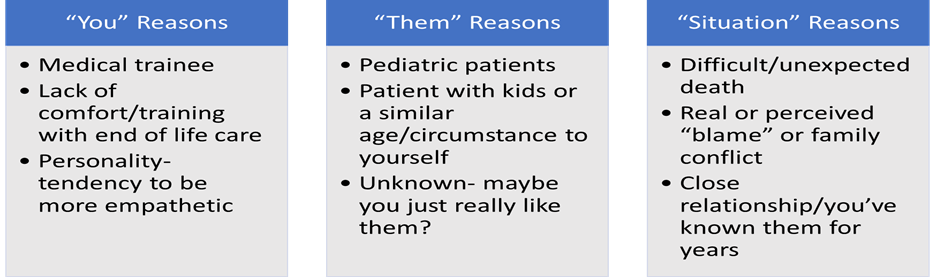

Almost all physicians have grieved the loss of a patient at one point in their career. Although grief can be a normal, universal human experience, physicians often do not discuss their own personal emotions and experience in relation to patient death. Discussing our own emotions with regards to patient loss is often seen as “taboo”, and therefore proper recognition and management strategies are evaded. Physician grief can lead to empathy burnout, mental health concerns and avoidance of end-of-life care. There are many factors that contribute to a physician’s risk of grief following a patient’s death. These factors can be broken down into the following categories:

Studies have shown that learners are at a higher risk of grief than practicing physicians. Therefore, medical education of both medical students and residents should include strategies to recognize and cope with grief throughout their training.

There are many proven ways to manage our own personal grief surrounding patient death, both before and after the death occurs. (Such strategies can be broken down into before a patient’s death, and after a patient’s death.) Before a patient’s death, we can improve our own and our learner’s comfort with end-of-life care through teaching and education. We can become more self aware- exploring the factors involved that may lead to grief in ourselves and our learners by using the above chart as a guide. We can practice self care and support our learners to do the same. We can also explore our professional quality of life by creating a safe environment for ourselves, our learners and our staff.

After a patient dies, we can participate in a process called “death rounds,” which is a time set aside at regular intervals to debrief on patients’ deaths and our own personal emotions. We can offer informal grief support to our learners and staff. Self care and healthy coping strategies are proven to be beneficial after the death of a patient as well. The writing of clinic obituaries can be therapeutic to physicians, health care staff and learners. And lastly, when used in an appropriate manner, humour has been shown to be beneficial.

References

- Dowling T. Compassion does not fatigue! Can Vet J. 2018;59(7):749-750.

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Physician grief with patient death. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(4):22-26.

- Gagnon B, Boyle A, Jolicoeur F, Labonté M, Taylor K, Downar J. Palliative care clinical rotations among undergraduate and postgraduate medical trainees in Canada: a descriptive study. Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal. 2020;8(2):E257-E263.

- Smith L, Hough CL. Using death rounds to improve end-of-life education for internal medicine residents. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):55-58.